The relationship between language disorder and thought disorder: Comparing micro- and macrostructure of spoken narratives of people with aphasia and people with schizophrenia

What is the relationship between language and thought? Do we think in whichever languages we acquired, or is language merely a code for translating thoughts for communication? These questions are millennia old, but today, they matter beyond our curiosity about the human mind or the structure of our brains. As we close in on solutions that help us detect mental health disorders, or dementia, by the way a person speaks, our understanding of the nature of language and thought becomes a practical, applied issue. Which features of someone’s language inform us about their cognitive health? I think this new publication, in which we compare language production in aphasia (a language disorder) with schizophrenia (a disorder of thought), offers some exciting insights. Or, at the very least, that’s what I hope, because this paper has been very difficult to put together and we all like it when hard work gets recognized.

Better known answers to questions about language and thought, such as Fodor’s Language of Thought hypothesis (language translates thought) or the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis (our language fundamentally enables and limits our thoughts), are too broad for our purposes. They either do not distinguish enough between individual features of language (grammar, lexicon) or between features of cognition. For example, we should not generalize arguments that mental rotation of objects may be independent of language to the vast expanses of human thought. The relationship between language and thought is likely more intricate and may vary depending on which aspects of each we choose to relate to one another.

A further source of variation comes from the data themselves. Broadly speaking, data from different clinical populations appear to suggest different degrees of relationship between language capacity and other cognitive resources. For example, people with aphasia can have very severely impaired language following brain injury but preserved other capacities (maths, social reasoning, navigation…). People with schizophrenia can have a wide range of cognitive disorders, from hallucinations to delusions and very disordered thoughts, alongside impoverished or disrupted language. Our comparison between those two populations helps identify which language profiles can be associated with thought disorder, and which not. This is not the first time we directly compared these groups. A previous study looked at results of standardized tests (see this older blog post).

The Dinner Party (Fletcher & Birt, 1983)

We examined comic strip (“Dinner Party”) descriptions from speakers with aphasia, speakers with schizophrenia, and because each group differed in age and local dialects, two respective control groups from the same regions and of similar age spans. Our language analysis is quite exhaustive, covering 23 variables in total and making a distinction between two levels of discourse: “microlinguistic structure”, which covers grammatical and lexical features, and “macrolinguistic structure”, which is concerned with how much information is communicated, how common it is for an element of the comic strip to be mentioned, and how much the order in which propositions (individual pieces of information which make up the story, e.g. The couple prepare the food) resembles what we see in controls. On macrostructure, we present some methodological innovations about which I will write in a future post.

We ran three different analyses: we compared groups directly, used machine learning classification to see how different sets of variables can help train a computer to distinguish between groups, and finally looked at the relationship between our linguistic variables and the results from common tests for assessing language and cognition (such as picture naming, non-verbal reasoning, making semantic associations). All three analyses tell a pretty clear story.

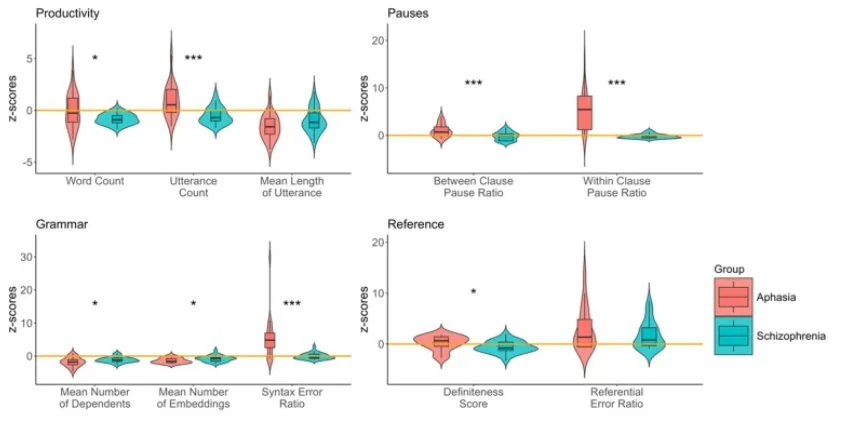

Both people with aphasia and with schizophrenia differed from healthy controls on micro- and macrostructure. For example, both groups produced simpler sentences, and presented aspects of the story in the comic strip in a non-typical order. However, our participants with aphasia struggled more with microstructure while performing better at the macrostructural level. Their sentences were even simpler, they made a large number of grammatical mistakes, made more pauses in the middle of utterances, but communicated a lot, despite these shortcomings. People with schizophrenia showed the opposite pattern. They appeared to have fewer issues putting together sentences, did not make many grammatical errors but communicated less. In aphasia, the relationship between micro- and macrostructure was weaker, and measures of aphasia severity correlated more with microstructure measures. In schizophrenia, the relationship between micro- and macrostructure was stronger, and measures of thought disorganization, semantic processing and non-verbal reasoning correlated with measures from both levels.

Some of our microstructure results (zero represents the control mean for a given variable)

A very simplified summary could be that people with aphasia generally know what they want to communicate, and aim to use their very limited lexical and grammatical resources to get that content across. Their data are generally consistent with assumptions that a relatively preserved propositional system of thought is trying to cope with an encoding bottleneck. People with schizophrenia appear able to produce richer sentences with less effort, but fail to use these resources to generate a successful narrative, likely because their propositional system is disrupted. Perhaps as a result, language production in schizophrenia is a clearer window onto broader cognitive disruption.

I think such a summary is more or less in line with what colleagues who are working in this area would expect. However, our direct comparison, embedded within a short review of the relationship between language and thought in other clinical groups (different dementias, Williams syndrome), can lead to a proposal on how to identify whether language decline is more a disorder of language or of thought:

If a speaker makes many grammatical errors and struggles in the middle of utterances, we are looking at a disruption of grammar and lexical processing, with other cognitive resources (relatively) preserved.

If there are few grammatical mistakes but we see simpler grammatical structures and odd lexical choices, we are likely looking at disruption in semantic processing and/or executive function which affects a person’s ability to engage in propositional thought.

I wrote earlier that this paper has been difficult to put together. All authors contributed a substantial amount of work, and Wolfram Hinzen was a very attentive project PI, always offering strong guidance; his ideas were essential to the project. When it came to data analysis and writing the manuscript, much of the hands-on work naturally fell to the three of us who were postdocs at the time of this project. Career changes, the Covid pandemic, and other challenges meant people became less available to work on this, and the longer results sit, the harder it is to pick them up. For too long, this unfinished paper felt like a real burden, or a curse. I at least had to finish it to live a little more lightly and to not let co-authors down. A real breakthrough came when Andromachi Tsoukala offered to work on the macrostructure levels. This brought new life and purpose into the work and made the paper much stronger.

The other challenge came from a team in which individual members had very different ways to talk and think about language and thought, working with different definitions and different frameworks. The (challenging) solution, I think, is to discard the big labels and explain in a clearer and more specific way which aspects of language, or communication, and which aspects of thought are currently under investigation. I hope that the approach to overcome this obstacle made the paper stronger. Understanding how language reflects thought can help us better detect cognitive changes and design interventions that truly address the underlying challenges.